An Introduction from the Author:

After all the events and publicity in the media over the last 12 months, connected to the 40 years since the end of steam on British Railways, I was delighted to be given the opportunity to put this book together, showing how the railways have changed in the 40 years since 1968, with particular emphasis on the 1980s and 1990s.

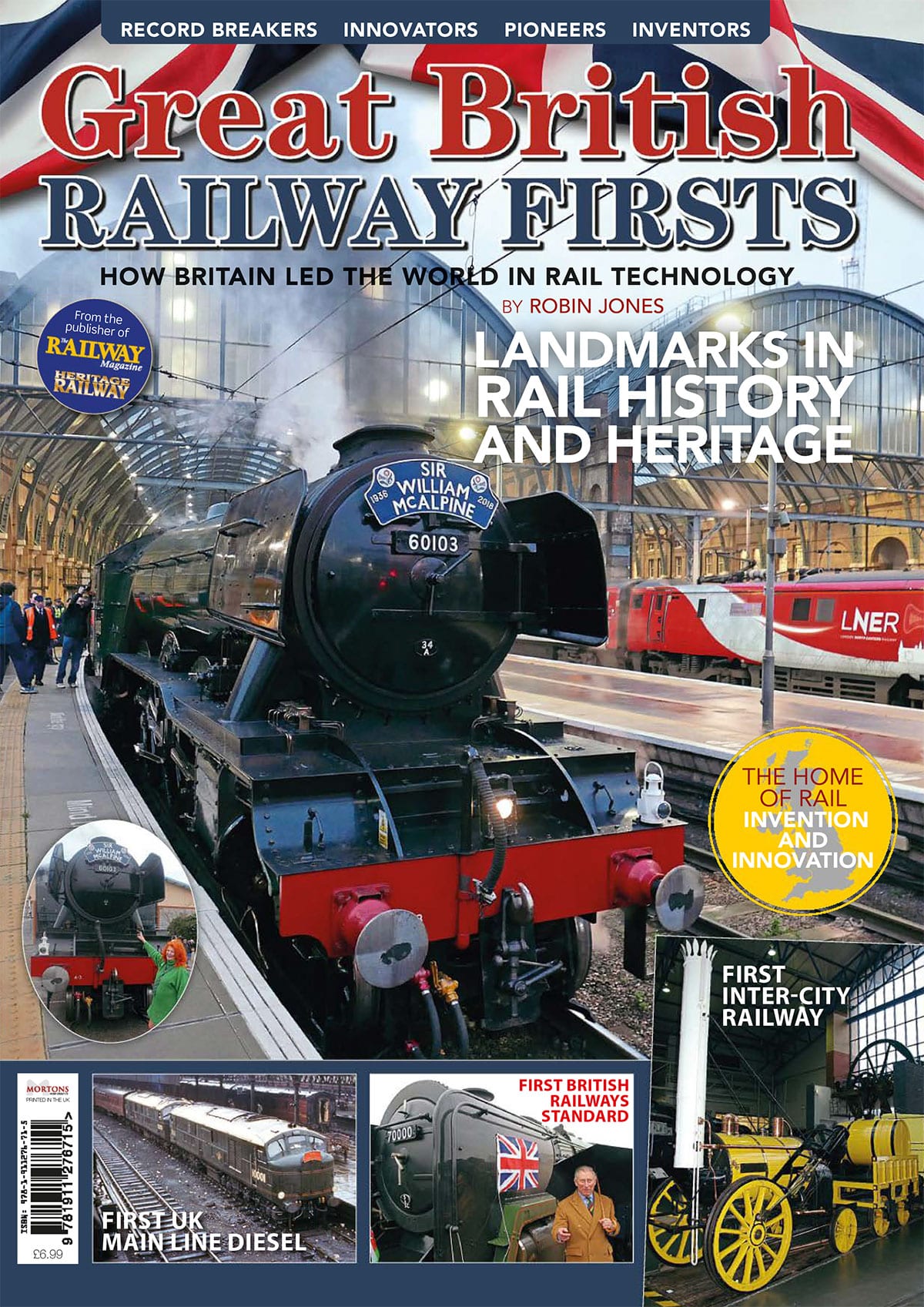

Whilst the public’s appetite for steam in preservation and on the main line shows no signs of dwindling, it is to the great credit of Network Rail and many others that steam can still be seen over most parts of the country, especially at places such as on the East and West Coast main lines where the 125mph railway exists. The public’s expectations of train travel in 2008 is quite rightly much more demanding than back in 1968 in terms of comfort, frequency and speed.

Railways after 1968 did not change all that much except for a few exceptions until the arrival of the HSTs as far as the travelling public was concerned. These trains completely changed the expectations of the public, and indeed saved the railway passenger services from what could have become a disastrous decline.

Gradually from the mid 1970s to the 1990s, the railways completely changed in character. The old infrastructure such as signal boxes and old style level crossing gates gradually disappeared, the singling of many lines took place, and the number of un-manned stations increased dramatically resulting in a railway system being run from main control centres rather than the local areas/stations. Whilst this undoubtedly had the advantage of reducing costs, one of the downsides was that because there were so few railway employees around, vandalism increased dramatically in many areas.

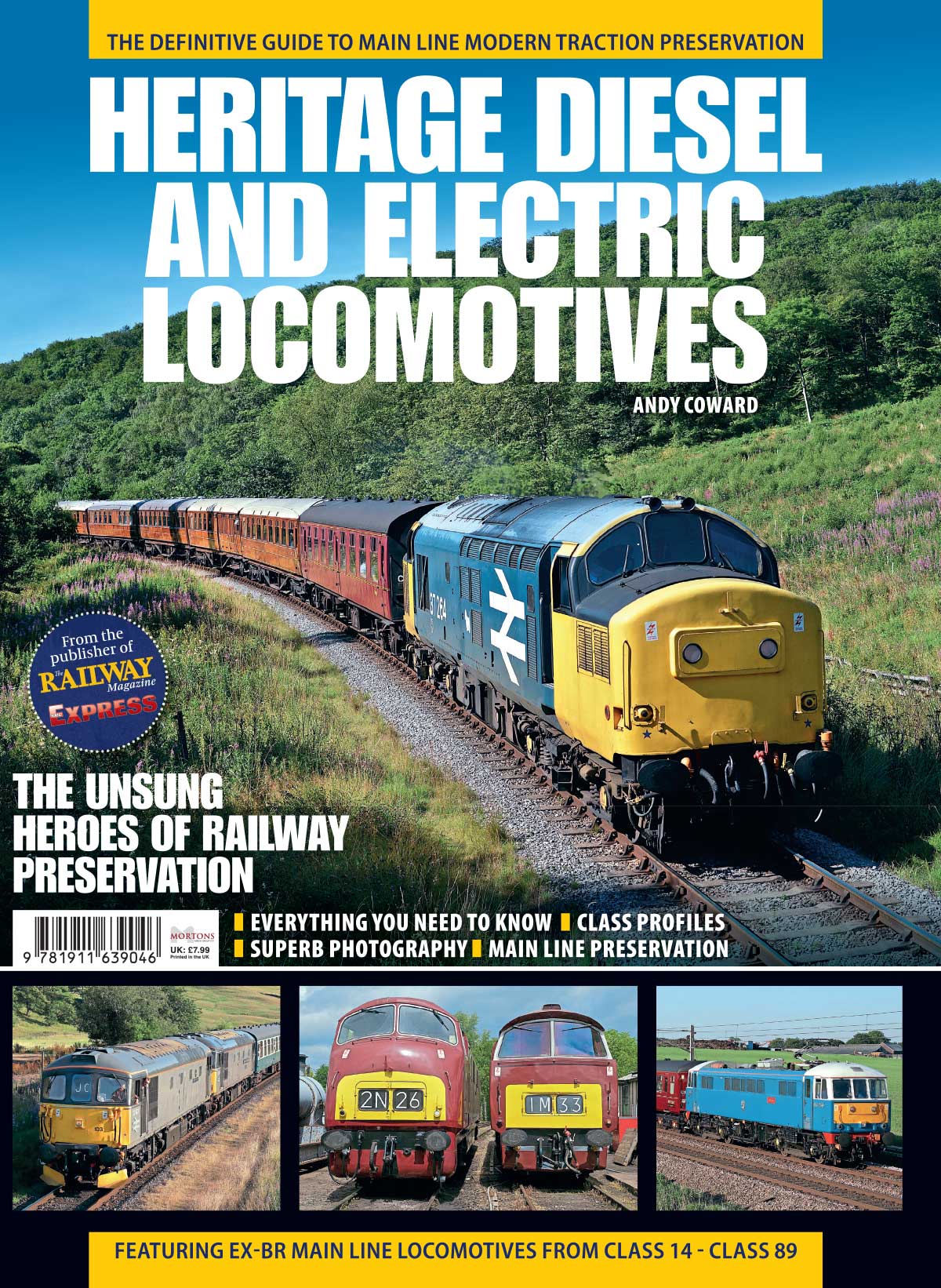

As the diesel and electric multiple units increased in numbers, so the quantity of locomotives declined, resulting in the closure of many maintenance depots, and main line workshops, although a few still remain but in a very much reduced form. There is only the need for a few works where major work on diesel/electric refurbishments can be done, as most other maintenance can be carried out very quickly at the maintenance centres, since the design of modern stock is all about keeping it running with the minimum of downtime.

After years of decline, the railways in the last 10-15 years have enjoyed a great increase in usage, so much so that line capacity and sufficient rolling stock has become a major problem in many areas. All credit must be given to the Train Operating Companies for developing the fantastic demand, through marketing effort and far more services and also in many cases achieving punctuality figures in excess of 90% for arrival times, but this has caused very bad overcrowding with some passengers having to stand for long periods on some services, but at the moment the Department for Transport does not seem to have come up with a solution to the problem.

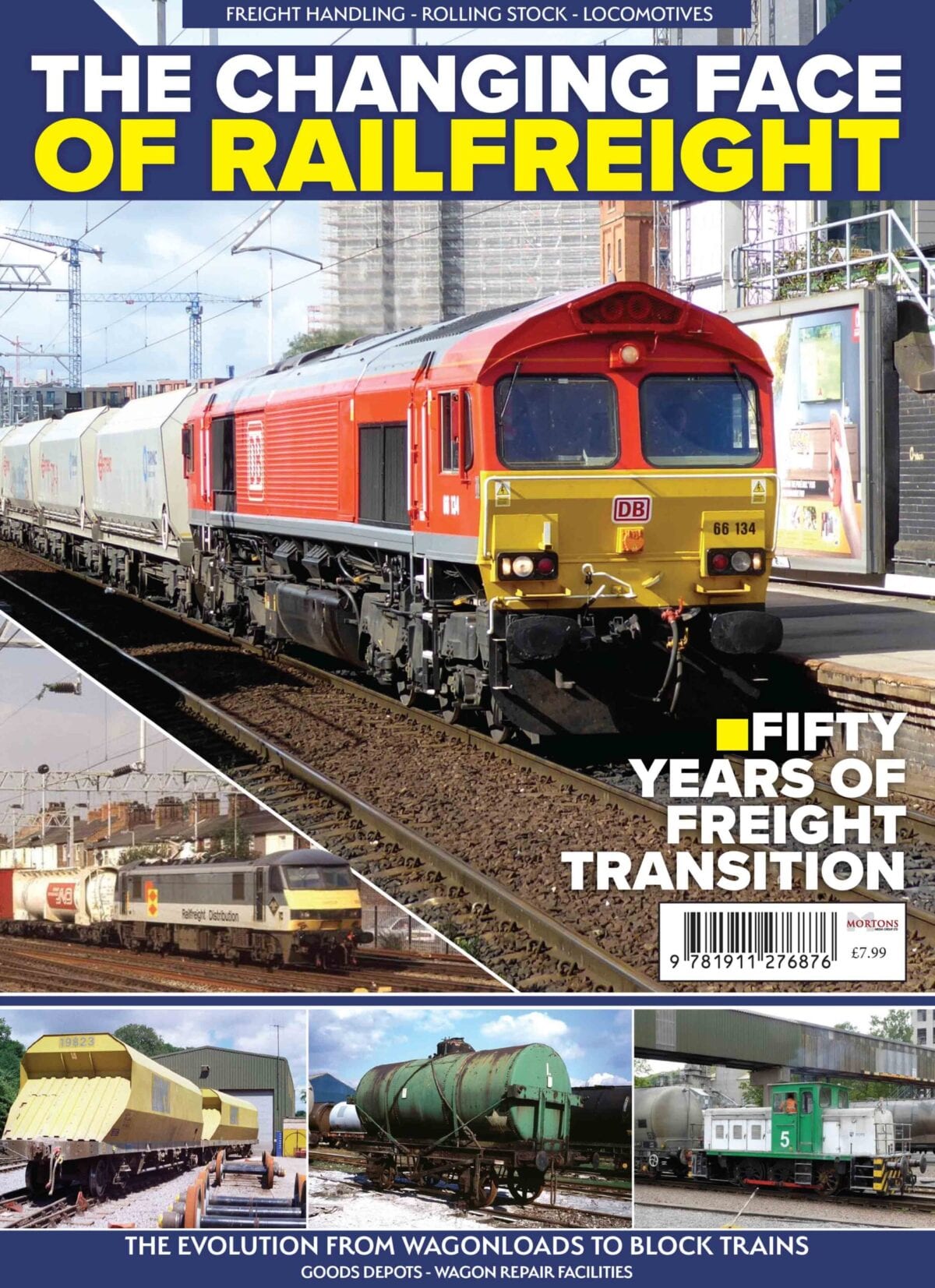

For the enthusiasts, whilst many will mourn the vast decline in the number of locomotives around, and the standardisation of the classes, eg Class 66s, on the positive side we have never had such a high level of train frequencies in most areas, and the abundance of attractive liveries has certainly brightened up the railways from the BR standard blue era, in spite of the cost involved in altering liveries every few years as differentTOCs take on new franchises. If anybody back in 1968 had suggested to me that in 2008 we would be seeing a brand new Class A 1 Pacific being run in ready for work on Network Rail, or that there would be tilting Pendolinos offering a 20-minute interval service from Manchester to Euston, and that Brussels/Paris would be around two hours from London travelling at 186mph across Kent, I would never have believed them, particularly if you considered how little the railways had really changed between 1928 and 1968.

Who knows what 2048 will have in store for railways and transport, the only thing certain is that unfortunately I will not be around to see it.

Author: Gavin Morrison