In the Thirties, Britain – like many other western nations – reeled under the effects of the Great Depression, with mass unemployment… especially in Scotland and the north of England.

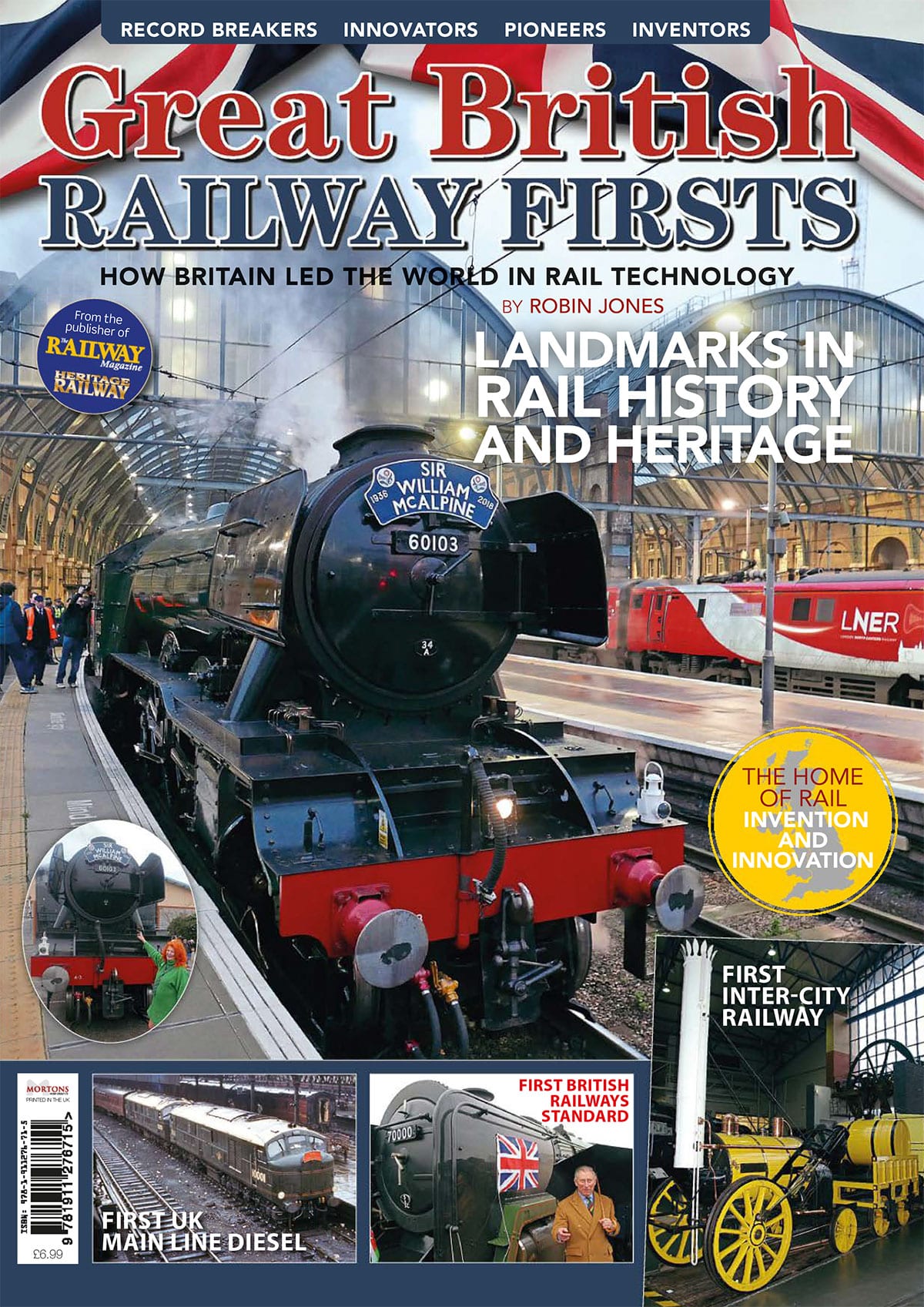

Yet out of the gloom and despondency, the people of these islands proved that we could still take on the whole world … and win.

It was on the 1-in-200 Stoke Bank, a seemingly unremarkable and very rural section of main line railway in Lincolnshire, that world steam locomotive speed records would come tumbling.

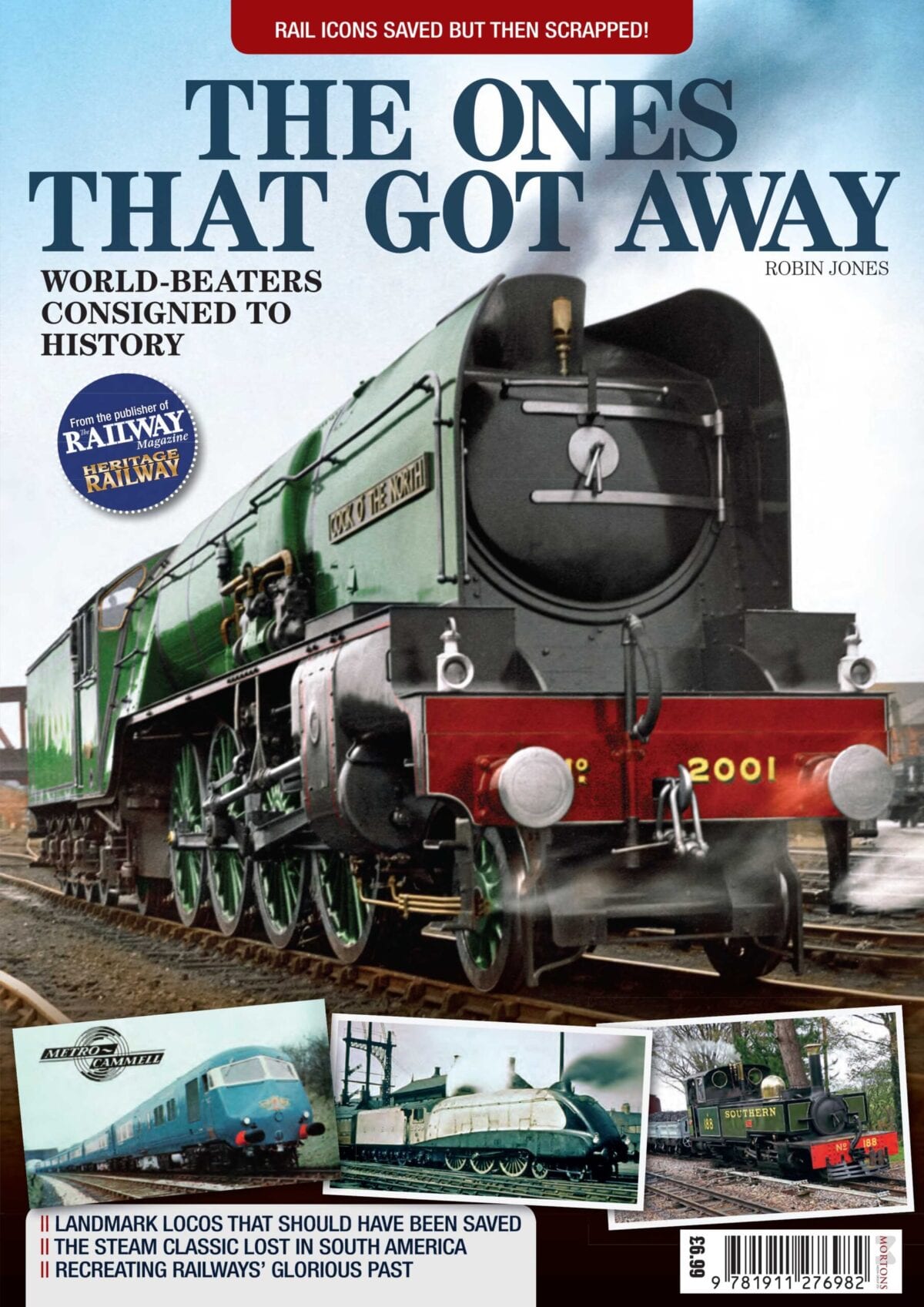

First there was Flying Scotsman, which in 1934 became the first steam locomotive in the world to officially reach 100mph. Then sister locomotive Papyrus set a new record of 108mph.

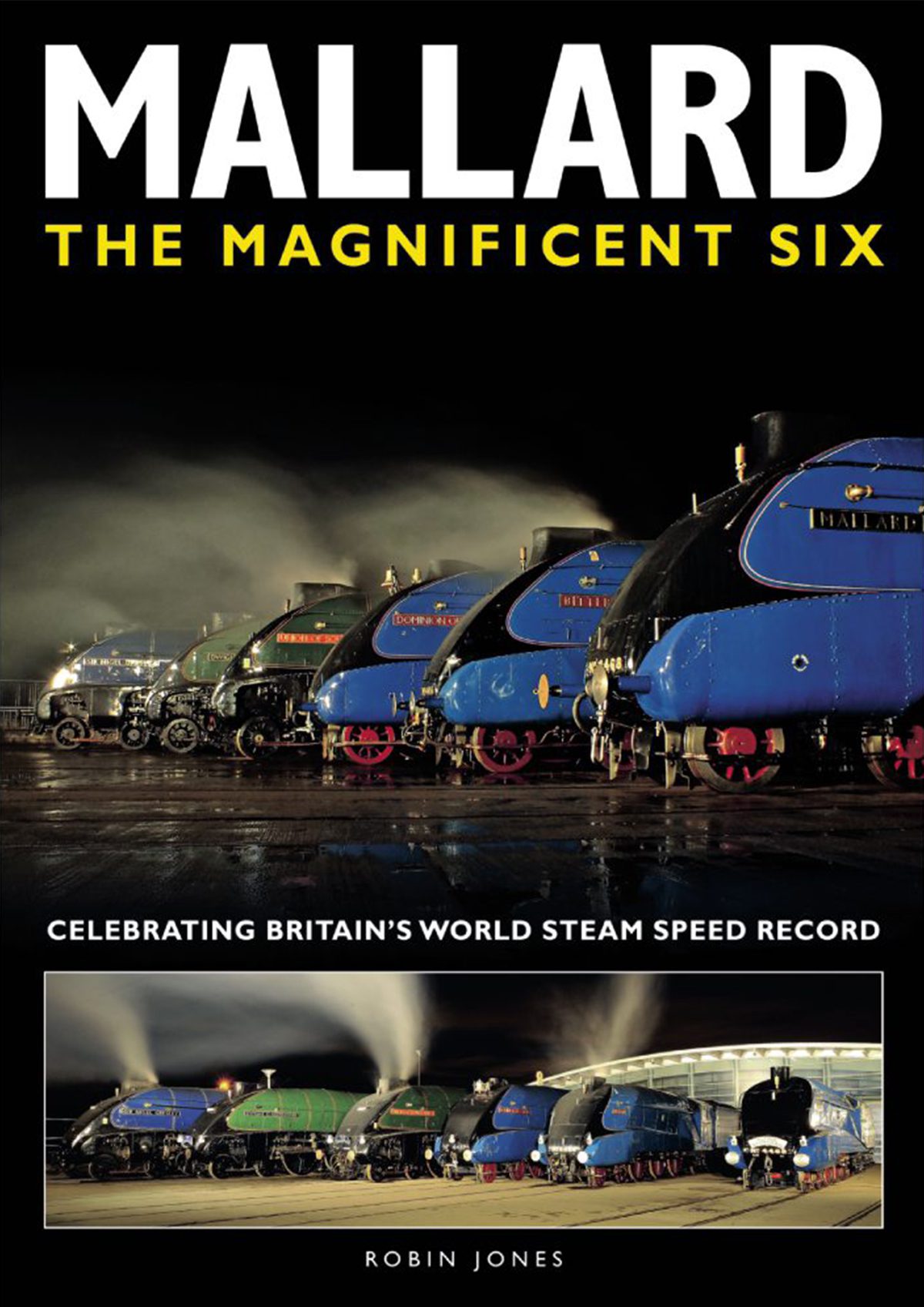

It was followed soon afterwards by streamlined A4 Pacific No. 2509 Silver Link, which managed a speed of 112.5mph.

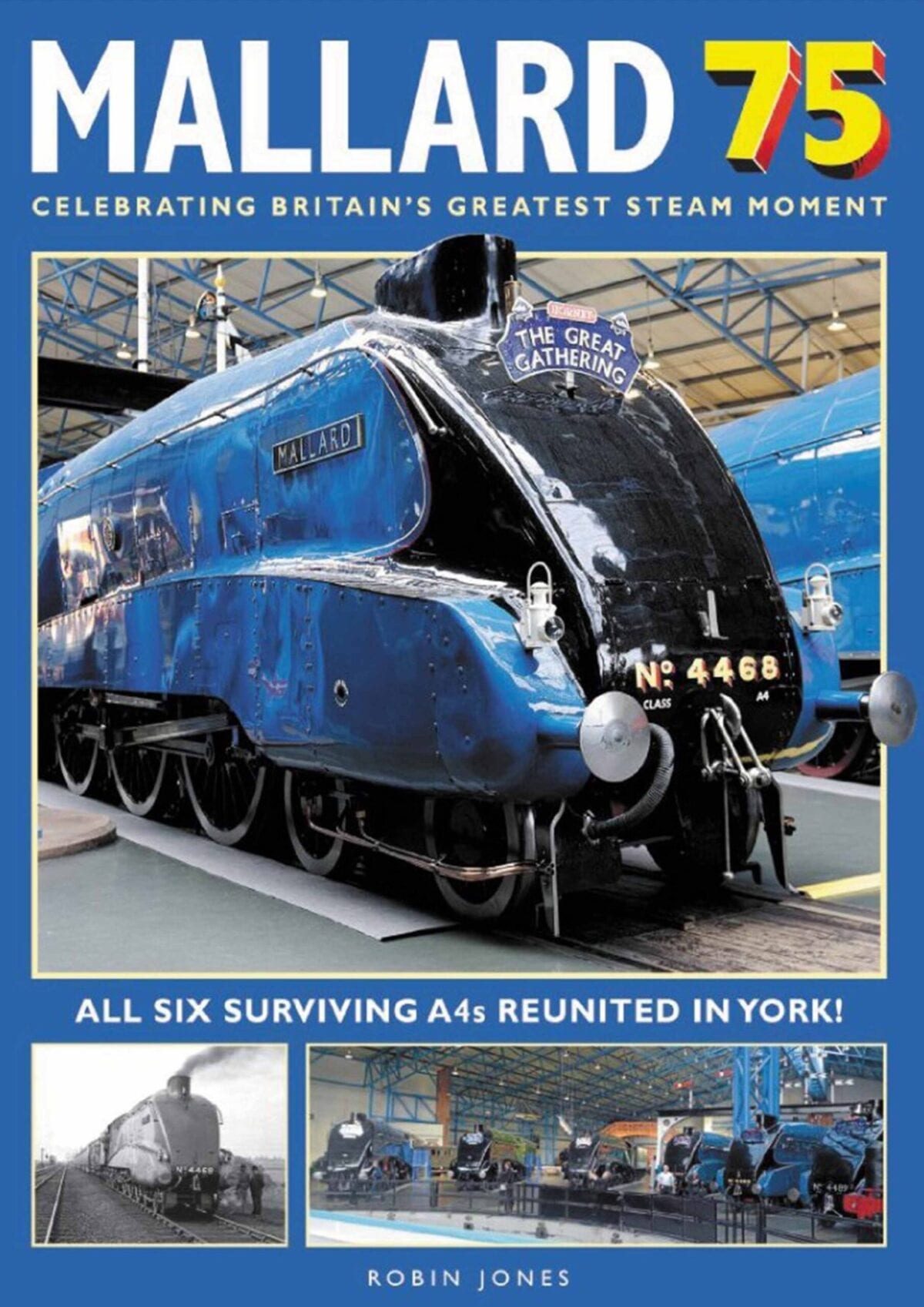

Finally, there was No. 4468 Mallard, which set an all-time world steam locomotive speed record of 126mph.

The man behind these legendary feats which emphasised the Great in Britain was London & North Eastern Railway chief mechanical engineer Sir Nigel Gresley. He designed these and many other groundbreaking locomotives which were superior to everything that had gone before.

The economic morass at the beginning of the decade could so easily have led to a situation where everyone might have given up hope.

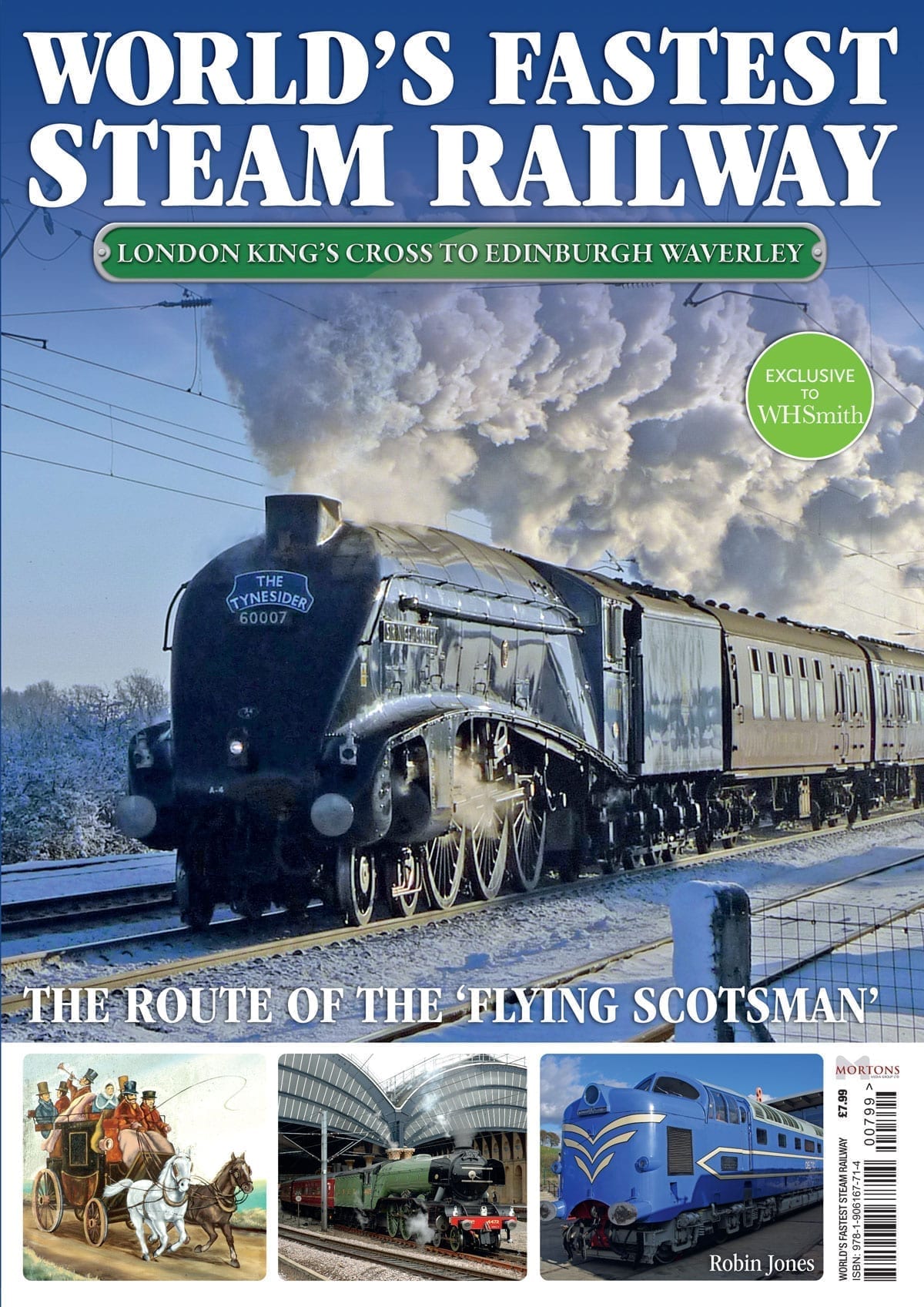

Yet it was still a great age of competition, one in which the LNER, as the operator of the East Coast Main Line between London King’s Cross and Edinburgh, wanted to show that it could link England to Scotland faster that the London, Midland & Scottish Railway’s West Coast Main Line alternative from St Pancras to Glasgow, and the splendid Pacific locomotives designed by Gresley’s great rival, Sir William Stanier.

The net result was the golden age of rail travel, in which luxury named trains such as the ‘Coronation’ and the ‘Elizabethan’ blazed a trail towards what should have been a bright new future, had the Second World War not intervened.

Gresley has been feted as the greatest British locomotive engineer of all time. Yet it was ordinary British footplate crews, drivers and firemen, who took his machines towards their limits – and beyond – in classic feats of derring-do and endurance.

Those behind the controls of a record-breaking locomotives would be feted as heroes by the national press when they returned to King’s Cross. They were the superstars, the pop idols, of their generation. However, the next day they would be back in their overalls on their next turns of duty, likely to be on run-of-the-mill scheduled services where superlatives were not necessarily required.

As Britain beamed with pride at such achievements, other nations looked on with awe and envy.

This volume is the story not only of those famous locomotives which became household words, but of the route from London to Edinburgh – from Roman times onwards – and how human endeavour, innovation and excellence shortened the journey times between these two capital cities.

There was the Great North Road and its rival stagecoach operators, which went out of business when three railway companies eventually joined up to create one great 393 mile through route, and almost immediately looked at the issue of speed.

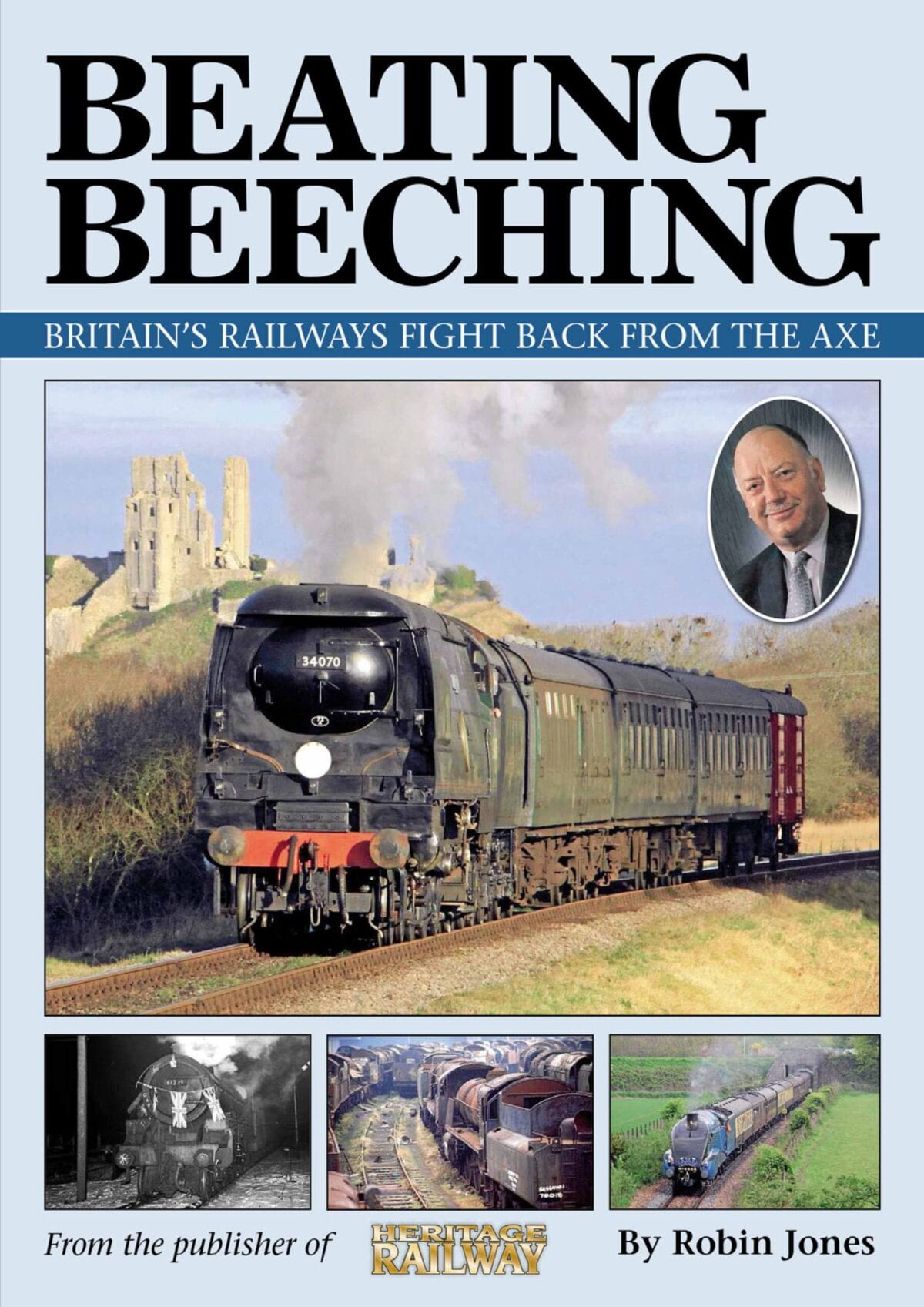

The steam age did not give up without a fight: in 1959 A4 Pacific Sir Nigel Gresley, named after the genius designer, recorded a new post-war steam record of 112mph – where else but on Stoke Bank.

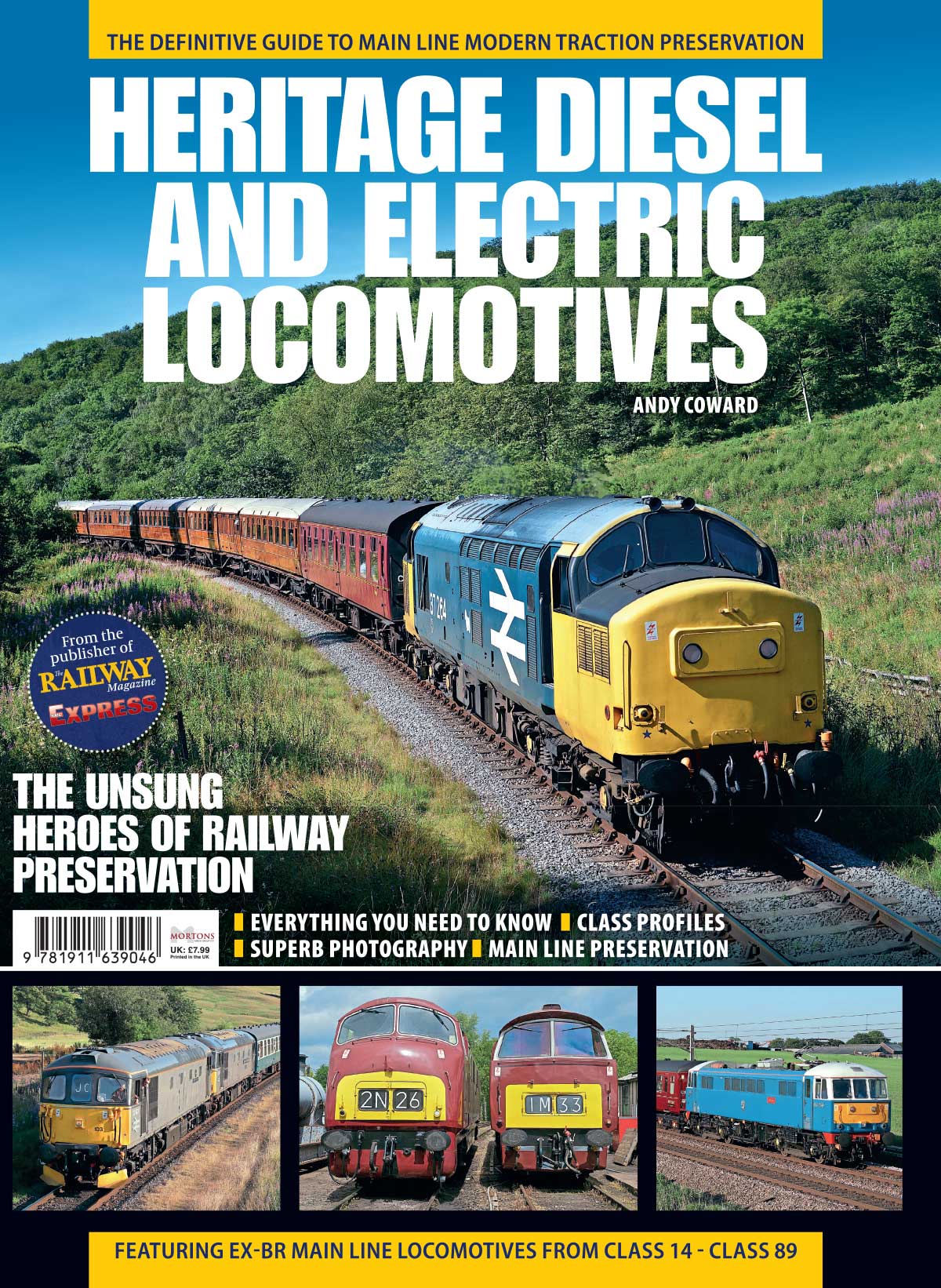

The diesel era not only produced some of the finest examples of modern traction in the form of the English Electric Deities, but also saw more records broken with the introduction of the hugely-successful InterCity Class 125 High Speed Trains.

Finally, the electrification of the whole route led to a Class 91 locomotive officially being declared the fastest in Britain.

The East Coast Main Line is taken for granted by the untold tens of thousands of commuters and travellers who use it on a daily basis.

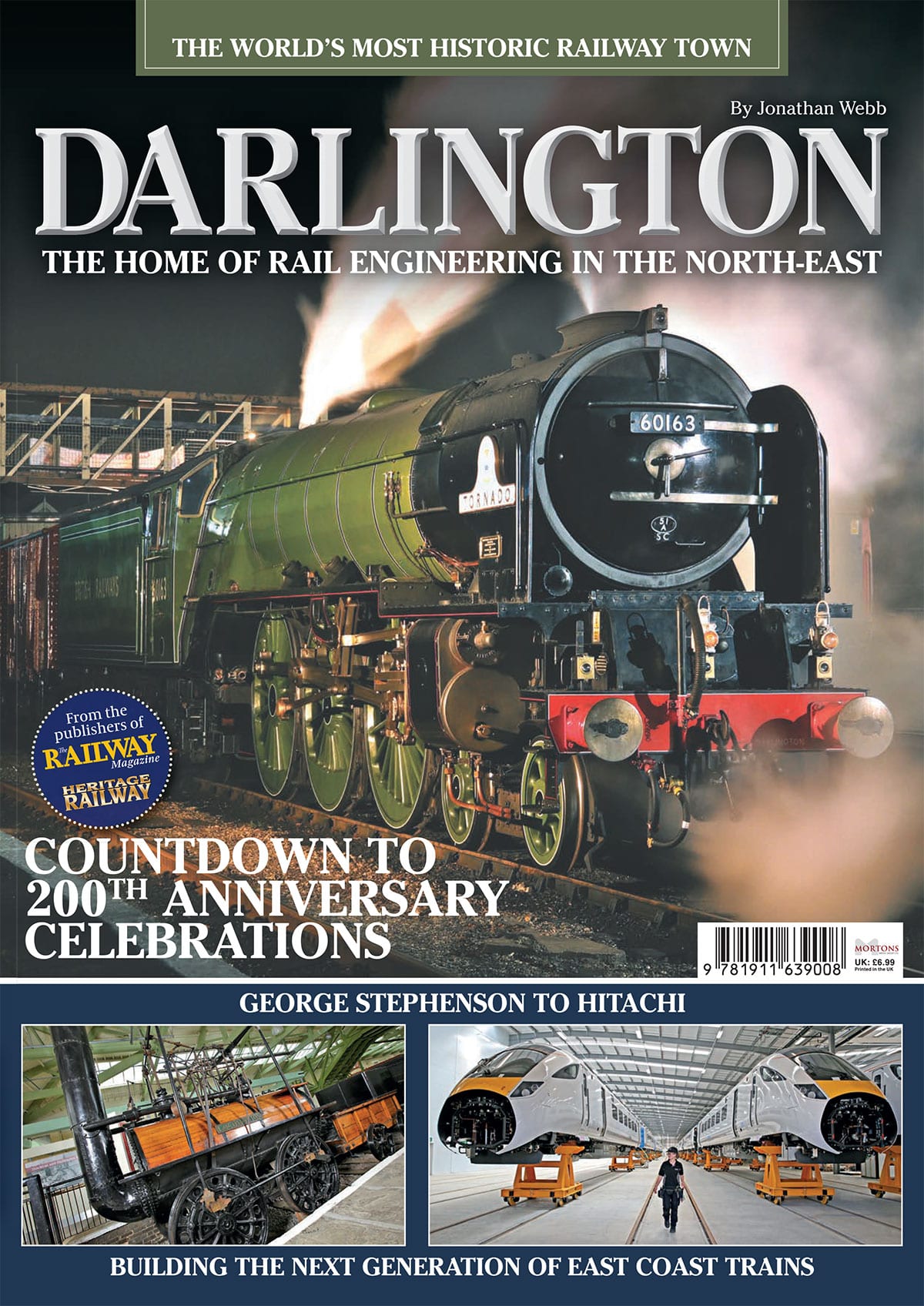

Yet it is a great monument, not only to those who built it- in the days when picks and shovels not JCBs and earthmovers were used to dig cuttings and create massive embankments by hand – but to many generations of railwaymen who showed on a daily basis that they wanted their line to be the best.

Gresley’s art deco streamlined A4 Pacifies remain a definitive icon of everything that was brilliant about Britain – a nation of innovation and determination which could so easily lead the world again.

Author: Robin Jones